Maintaining true crime’s momentum

ACCLAIMED Netflix series Making A Murderer triggered an explosion of interest in true crime. Today, it’s arguably the most popular subject on television – bridging both scripted and non-scripted. The genre isn’t going away anytime soon, but just how do producers and broadcasters keep it fresh?

There are four clear trends going on in the genre. Firstly, increased and improved access to perpetrators. It’s chilling, for example, to listen to Lee Boyd Mavo’s first-hand account of the Washington DC sniper killings in the Netflix series I, Sniper – or the testimonies of convicted murders in I Am A Killer. These days, there’s almost no point in making a high-end true crime series if you can’t get the killer on audio or videotape.

Secondly, there seems to be a concerted effort to show more respect to victim and their families, rather than just treating them as necessary props. Again, this is evident in I, Sniper – but it’s also apparent in hit series such as The Keepers, a tasteful exploration of the death of nun Catherine Cesnik.

Thirdly, led again by Netflix, there’s a move to internationalise the genre. The Motive, for example, explores the case of a 14-year-old boy who shot his family in Israel in 1986. Currently there are also shows from Spain (Where Is Marta?), Brazil (Elize Matsunaga: Once Upon a Crime) and Ireland (Sophie: A Murder In West Cork). Not so long ago Canadian true crime doc Don’t F**k With Cats: Hunting An Internet Killer was also a big hit.

Finally, there is currently growing interest in ‘stranger murders’ – evidenced by shows like Murdered At First Sight. Produced by Woodcut for Sky in the UK, and distributed by Abacus, this ten-part series tells stories of seemingly motiveless murders. Notoriously difficult to crack, they are on the rise. “The fact that these perpetrators commit heinous acts on strangers is hard to comprehend,” executive producer Matthew Gordon says. “As producers, we always try to explore the stories with sensitivity.”

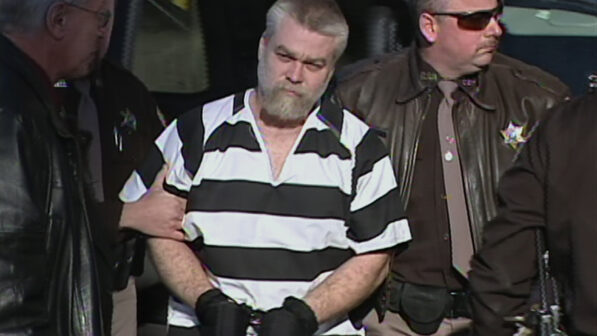

Making A Murderer. Photo: Netflix

Building format worlds

WHEN TV execs talk about world-building, they are generally thinking about richly constructed scripted series like Game Of Thrones or Breaking Bad. But some of the world’s leading entertainment formats are now such powerful brands that they too have a kind of world-building dimension to them. BBC 3 in the UK, for example, has just commissioned RuPaul’s Drag Race: U.K. Versus The World. This is the latest extension of a brand that has worked extremely well both as a format and a scripted series on the international circuit. In a similar vein, Fox in the US has enjoyed a run of success with The Masked Dancer, a spinoff from its wildly successful predecessor The Masker Singer. Junior versions, senior versions, celebrity versions, pan-regional versions, secondary channel spinoffs and behind-the-scenes shows are all part of the rich tapestry of formats. Banijay’s MasterChef, for example, has spawned a similar range of spinoffs – as well as a series for teens and a series for working chefs, MasterChef: The Professionals.

Further supporting these powerful format ecosystems are international versions. Shows like MasterChef, Married At First Sight and Got Talent have generated such a loyal audience that fans are willing to watch versions created for other countries. UK broadcaster Channel 4’s youth-oriented service E4, for example, has enjoyed a good run with the popular Australian edition of Married At First Sight. Where else can these format juggernauts go? Fast channels, live events, licensing, publishing, games, NFTs and social media are all opportunities – and so perhaps is the emerging metaverse. Leading formats have become invaluable brands in the streaming age – and many will outlast the channels that provided them with launch pads in the first place.

Mike Tomkins, Alexina Anatole and Tom Rhodes were the BBC MasterChef finalists 2021

Putting celebrities to the test

WE’RE ALL used to seeing celebrities on television – but with the occasional exceptions like I’m A Celebrity, Get Me Out Of Here and Who Do You Think You Are?, they are usually given the Hello Magazine treatment. Everything is built around their latest project, their philanthropy, dining with friends, or giving them the opportunity to try something new – ballroom dancing, for example. There is a sense, however, that this is no longer enough for audiences. These days, viewers either want to see celebrities pushed to the physical limit, or challenged emotionally. This development is evident in a couple of recent commissions. Disney+, for example, has just commissioned a National Geographic show called Pole To Pole, that will see Will Smith travel from the bottom to the top of the planet. Obviously, at one level, this is a great opportunity for Smith to gain some experience that most others wouldn’t be able to engage in, but it will also be an arduous adventure which should show us more nuanced version of his personality, not dissimilar to Zac Efron’s Down To Earth.

As for the trend towards emotional discovery, BBC1 has just commissioned Unbreakable (working title) in which celebrities and their partners face a series of challenges designed to test the strength of their relationships. “Our other celebrity-driven formats have tended to be light-hearted specials,” says the BBC’s factual entertainment chief Catherine Catton. “Putting celebrities under pressure, setting emotional and physical challenges that bring their relationship dynamics to the fore, and ultimately scrutinising who has the strongest bond, feels like new territory.”

The changing face of dating formats

THERE HAS always been a dichotomy in the way factual entertainment deals with dating and romance. At one end of the spectrum are aspirational shows like Love Island, FBoy Island, Too Hot To Handle and Ex on the Beach which perpetuate certain notions about desirable body image and the nature of attraction. At the other are reality-led series which get to grips with the more complex and poignant nature of desire and relationships. Catfish, Wife Swap, Married At First Sight and Farmer Wants A Wife are all examples of this – but more recent illustrations include Love Off The Grid and Prisoners Of Love. A big question right now is whether the former group are doing enough to really reflect the nature of their audience. In a world where Diversity, Equality & Inclusion (DEI) are increasingly viewed as non-negotiable by Gen Z and millennial audiences, do producers and broadcasters need to rethink the composition of their aspirational relationship-based shows? There is some evidence that the industry is exploring what to do in this area. MTV’s Are You The One? made a progressive stance when it commissioned a gender-fluid season in 2019. More recently, MGM’s Kinky Daters sent open-minded singles on dates with people who enjoy unusual kinks or fetishes, while Fremantle/Naked’s The Love Triangle matches singles and couples looking for the perfect ‘throuple’. The revival of Banijay’s Beauty And The Geek format by Australia’s Nine Network last year is also, arguably, part of this trend. Absent from the market for seven years, it captures the new zeitgeist around dating. Evidence that this is not a one-off, came this month when Discovery UK commissioned a version for Discovery+.

Giving natural history content a purpose

WILDLIFE programming has always been at the pinnacle of television production; combining elegance, insight, innovation and endurance. But increasingly it has looked displaced in a world hurtling towards self-destruction. Like zoos, it’s not enough anymore to say that natural history TV helps educate children about animals. Climate change, plastic pollution and diminishing biodiversity are all just too important to ignore in the pursuit of a great action shot. The BBC’s Blue Planet 2 was a turning point, alerting viewers to the scale of the ocean plastic problem. And now the UK pubcaster has committed itself to Our Changing Planet, which Patrick Holland, director, factual, arts and classical music television, calls the “most ambitious environmental series the BBC has ever commissioned.” For seven years, BBC Studios’ Natural History Unit will closely document six key habitats around the world, including California, the Arctic, the Maldives, and the Amazon rainforest. “These locations are bellwethers for the health of our planet,” says Holland. “As the series goes on, we will witness rapidly unfolding ecological change and observe surprising new animal behaviours as species adapt to their shifting environments.”

Netflix has also shaken up the genre with provocative series like Seaspiracy. But companies like Waterbear and WildEarth are also committed 24/7 to issues including climate action, biodiversity, sustainability and community. WildEarth, for example, recently launched an NFT programme directly linked to its conservation efforts.

Recent and future changes in natural history programming are not just about what’s visible onscreen – because location-based shows inevitably have a significant carbon footprint. Producer Plimsoll, recently commissioned by Disney+ to make Great Migrations, has put in place various mechanisms to support sustainable production.

The Gamification of TV

ATTEMPTS to create TV shows based on gaming brands don’t always gain traction – a recent example being CBS game show Candy Crush. But if we think of gamification in a more general sense then it is currently driving two key trends in the format business. The first is the emergence of shows based on childhood games that people just want to keep playing into adulthood. Lego Masters is the best example of this, but Marble Mania, Race Against the Tide and Floor Is Lava are all in this bucket too. As K7 Media points out, this is an international phenomenon, with Mexico having “Game of the Goose (El Juego de la Oca) based on a popular local board game” and “TV Asahi’s Red Light, Green Light based on a globally recognised children’s party game”. The second trend is a new wave of large-scale physical shows with a game-tinted narrative. In some respects, it’s no surprise physical shows are back – because they provide the perfect counterpoint to the lockdown years that most of us have been experiencing. But rather than just rely on the classics (Gladiators, Ninja Warrior, Wipeout), we’ve seen Viacom reboot Legends Of The Hidden Temple and The Crystal Maze – both notable for their immersive qualities. NBC’s Titan Games, RTL4 Netherland’s Traitors and Netflix’s Ultimate Beastmaster also tilt towards this trend. Obviously, the biggest thing that could happen in TV formats over the next couple of years would be an entertainment version of Korean hit Squid Game (though all the random murder and body harvesting mean the concept is probably more suitable for transition to the world of console gaming).

Ultimate Beastmaster Season 3

The golden age of music TV

A LOT HAS been made of the fact that, in the absence of live sport, the field of sports documentaries thrived. But the same is also true of music documentary. HBO struck gold with its music-based strand Music Box, produced by Ringer Films. A series of six feature-length docs, Music Box titles included the critically acclaimed Woodstock 99: Peace, Love, and Rage, and Listening to Kenny G. At the end of 2021, HBO ordered a second season of the strand. A point of interest is that Ringer started out as a website and podcast – created by Bill Simmons. It was then acquired by Spotify for $195m. So it’s a great example of how digital platforms can provide the impetus for TV content.

Other projects which point to a resurgence in music TV include Apple TV+’s acclaimed film about The Velvet Underground and Disney+’ The Beatles: Get Back, directed by Peter Jackson. An interesting note about Get Back, which runs to about eight hours, is that it is built around the unused audio and footage from a 1970 documentary, Let It Be. The implication is that there is more room on modern streaming platforms to explore subjects in depth. The original documentary, directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg, ran to 80 minutes. 2022 has started in a similar vein, with Lifetime’s hotly anticipated Janet Jackson documentary series airing in January.

Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney, John Lennon and George Harrison in the documentary series The Beatles: Get Back. (Photo: Apple Corps Ltd./Disney)

Covid-19 lockdowns revitalise UK gameshows formats

COVID-19 has been a tough time for many people around the world. But the disruption it caused does seem to have unleashed a new wave of creativity in the UK entertainment format business. There appear to be three reasons for this. Firstly, broadcasters were suddenly forced to find shows that could fill unexpected gaps in the schedule. One beneficiary of this was The Wheel, which was picked up by the BBC because it seemed relatively easy to make under COVID restrictions. The show was a hit and has since been picked up by NBC in the US and RTL Germany among others. Secondly, the pandemic created time and space for producers to develop new concepts. Shows to have come through during the COVID era include Limitless Win, Walk The Line and Moneyball on ITV, Bank Balance on the BBC, and Moneybags on Channel 4. Thirdly, the pressures created by the pandemic forced producers to think about whether their existing hits had spin-off potential. The result is shows like Fastest Finger First, a spin-off from the global hit franchise Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? There’s no doubt that some of the above will get picked up as formats by international broadcasters – but what do they tell us about the direction of the genre? Well, there is clearly a strong emphasis on prize money – perhaps because people have struggled financially during the pandemic. There is also a taste for hybrid concepts, with Walk The Line bridging game and talent. The UK also seems to have embraced the US tendency to parachute well-known talent from other fields, into gameshows as presenters – for example Jamie Foxx as presenter of Fox’s Beat Shazam in the US. This started a few years back when former British Top gear Jeremy Clarkson took over the Millionaire hotseat – and chef Gordon Ramsay on Bank Balance and comedian Michael McIntyre on The Wheel consolidate this trend in the UK.